Why teach literature?

At a time when information is measured in terabytes and the world is available on a smartphone, it is not surprising that English teachers are constantly asked why and if the study of literature really matters. But, perhaps, it has never been more important that it is today. For reading allows students to explore other worlds, other centuries, and other predicaments through the eyes of characters. Like the study of history, literature makes one aware of the abuse of power and privilege; of rampant prejudice and bias; like the study of history, it teaches tolerance and empathy. The study of literature encourages international mindedness; it enables global citizenship.

Is the classroom a place for teaching tragedy?

An IB student of mine once walked up to me and asked: Why does the English department teach so many ‘sad’ texts? Are there no happy ones? She was talking about our selection of partition and holocaust literature, Greek tragedy, and a well-known Latin American novella about the cult of machismo. I had to admit that the texts we had selected did explore dark themes (patricide, genocide, violence, racism and poverty) but will confess that I took refuge behind Tolstoy’s words: All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Looking back, I realise I should have told her that the texts we taught (both comic and tragic) enabled us to discuss ethical dilemmas and encourage student engagement with questions of social justice. That the texts we had selected were evocative, powerful and, quite simply, worth reading. If literature is about suffering; it is also about healing.

To Canon or not to Canon?

Over the past few decades, passionate arguments have been made for the partial replacement of canonical western texts with courses on world literature; for the inclusion of translated and media texts, graphic novels, slam poetry and hip hop songs in an attempt to retain student interest and ensure that courses remain relevant and do not alienate young learners the world over. In 2016, the Nobel Prize for Literature went to Bob Dylan ‘for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.’ Both Dylan and John Lennon have now made their way into prescribed texts lists of examination boards like the IB.

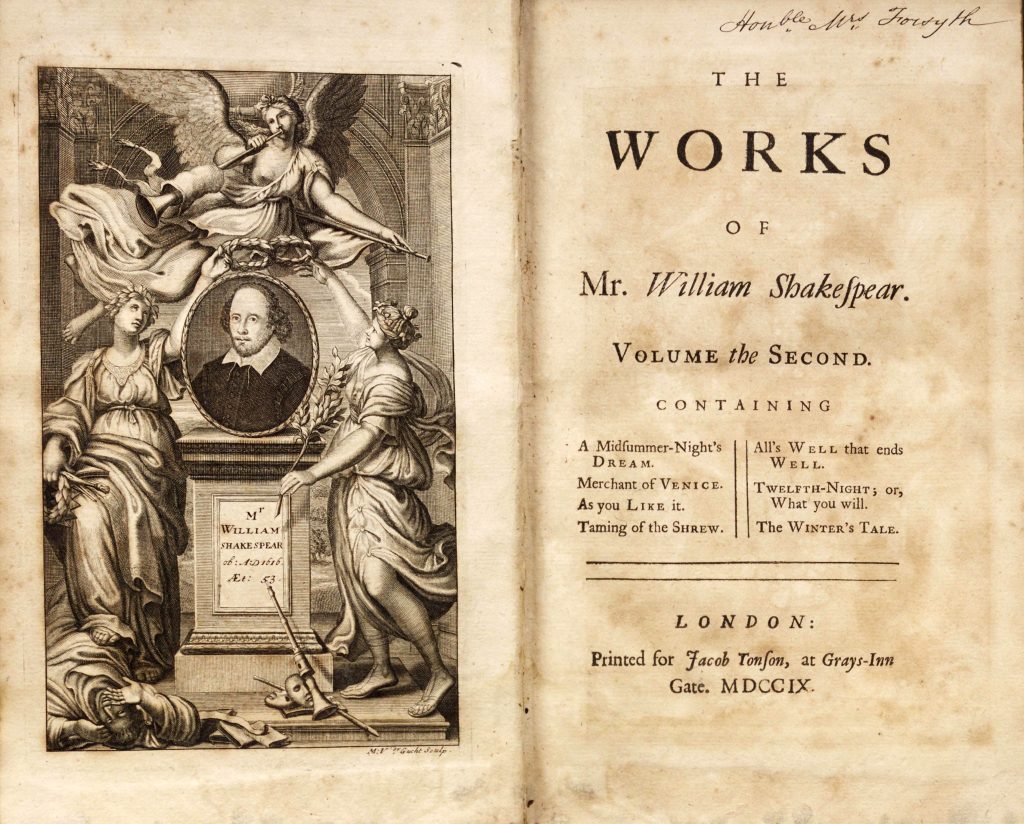

At TBS, as in English departments across the world, teachers, time and again, debate the merits of teaching the English literary canon. Should students irrespective of nationality and context be made to read Shakespeare’s tragedies, the poems of John Keats and the novels of Charles Dickens? Are there any real arguments to be made for teaching their works or are we, English teachers, merely serving an imperialist or euro-centric cause?

Surely, good teaching is all about making a wide range of texts accessible to students, helping them see their relevance, and enabling a better understanding of the past including the evolution of the English language. Shakespeare must be taught as we owe our students the challenge and believe in their ability to cope with complex ideas and texts. Equally important is the inclusion of marginalised voices and texts in translation in the English programme that allows for critical engagement with diverse cultures and world views.

Therefore, to look upon the English or the western canon and dismiss them outright would be fallacy as it would deprive students of our collective global literary heritage, just as much as the exclusion and silencing of voices from other cultures would do.

PS: Now that Dylan is part of the canon – should we look for newer, more radical, voices of protest?

Photos courtesy commons.trincoll.edu, unsplash.com and medium.com