The pandemic has caused the largest disruption in education: from school closures, bubbles and restrictions on resources to pressure on educationists to adapt to a virtual platform. However, it is fundamental to stress the achievements and opportunities the crisis has in turn created. Teachers have swiftly adapted to online teaching and their own CPD has flourished despite the difficulties and pressures. Parents involvement in their child’s education has increased through home-schooling and people have learnt to cherish simple pleasures such as walking, home crafts and dining out and socialising. The pandemic has understandably been an emotional see-saw for many, with highs and lows. But how have the youngest children been impacted?

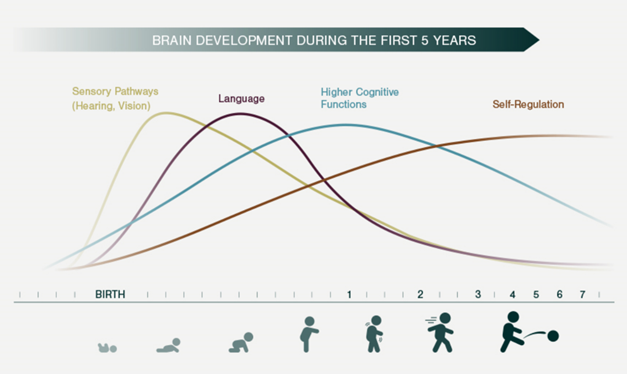

A baby’s brain will double in size in its first year, then increase to 80% by the age of three and then incredibly by the age of five, it is almost fully grown. It is no shock that the first five years of a child’s life are crucial. It is important to stress and recognise that not all pandemic babies, toddlers and preschoolers’ early life has been negative or damaging.

For many families, being home together was a unique and rare opportunity during which relationships flourished. However, it cannot be ignored that over the last two years notable changes have been recognised by early years practitioners when observing and facilitating learning for children under five.

Unsurprisingly, studies and reports have identified Communication and Language (CL) and Personal, Social, Emotional Development (PSED) as the prime areas that have been the hardest hit. The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has published two reports: The Early Years Toolkit with a focus on self-regulation and Preparing for Literacy which provides strategies to prepare children with the fundamentals to be secure communicators, readers and writers. These reports highlight how significant these early skills are in order for children to continue to develop and meet the expected milestones.

From my own experience I can relate to a significant shift in young children’s PSED skills, particularly the increase in their sensory needs. More children are fixated with messy play areas, likely because they lacked previous early years experiences due to settings being closed, and for many families having slime covering your kitchen floor is not an option.

There has been a recognition that children are struggling to share, take turns and establish true friendships. For many, Nursery or even Reception has been their first opportunity to socialise and meet other young children as families restricted themselves to household members.

Setting routines and boundaries has been a dilemmafor many parents as they may not have mixed at social events with their children or had playdates and outings. Therefore, the expectation of parenting has been limited and the pressures of being a ‘good parent’ (which I use lightly as there is no rule book or perfect parent model) have not been scrutinised by friends and family as parents have been hidden at home. We take advice and ideas from others when we socialise and it helps us reflect and adapt our behaviours. But these have been limited for many parents and families, therefore the repercussions are being displayed through young children’s behaviour.

As we know from Development Matters and Dr Julian Grenier’sThe Seven Features of Effective Practice, attributes like self-regulation need to be acquired and established for children to progress. Developing secure, trusting relationships between caregivers at home and educational practitioners is equally vital. If adults cannot relate, nurture and create a bond with a child, they will not share their feelings and worries, creating a barrier for further development. Hence, the triangulation between caregivers, practitioners and the child needs to be trusting and open.

With this is mind, it is pertinent to highlight why it is so important for children who have lived through the pandemic to have the skills to voice these feelings and emotions. Many of them have been isolated to their homes, which has created further problems for some as they have been exposed to their caregiver’s emotions and anxieties.

Walton and Darkes-Sutcliffe, 2021 highlighted that the mental health of children could not be separated from the emotions and behaviours of the adults responsible for them.

This is significant as it emphasises how crucial it is for EYFS practitioners to engage with parents, as this is more than just the child’s conundrum. Parental interactions, meetings and observations have verified this, where some people are scarred from the pandemic and this has been absorbed by their young children.

Practitioners need to be mindful that parents play a crucial role in the development of their child and if their mindset, wellbeing and skillset is impacted negatively and they are not equally supported, removing barriers for the child is worthless.

It seems imperative that services such as parent-toddler groups, parenting classes and creches are fully restored and with maximum funding if we are going to bridge the gap that the pandemic has inflicted on young children and their families. These services provide a means to foster relationships so parents and staff can have greater impact on the childand alsoprovide another layer to discourage any harm to young children as they offer safeguarding for children.

With the pressure of statistics, outlining children’s developing vocabulary and phonic awareness, it is surely evident that these young children need to develop relationships and social skills before we overload them with the pressures of early literacy. Ideally the two areas of concern go hand in hand, but early years practitioners need to facilitate and intervene with integrity rather than feel pressured with statistics. Their aim should be to deepen the skills of PSED and CL that in the long term will have greater impact on children meeting milestones, and then begin to bridge the pandemic gap.

The evidence from our own teaching experiences and research has exposed the importance of not rushing to plug gaps but to teach fundamental skills that not only ensure that children will develop and catch up to age appropriate milestones with time but more importantly, will be able to flourish in social arrangements.

The pandemic predicament can be seen as an opportunity to put into action what so much of the research for many years has outlined. If we have secure foundations for our young children, the other key skills will be built upon as the child develops.

Adults encourage children to be resilient every day and in this globally challenging environment, we need to be remodeling hope and endurance. Outwardly expressing that preschool children of the pandemic were born into challenge is not going to alleviate the predicament; it may be an obstacle but by seizing it with integrity and trust of what skills need to be secured first, children will thrive over time.

References

- The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), The Early Years Toolkit

- The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), Preparing for Literacy

- Dr Julian Grenier, Working with the revised Early Years Foundation Stage, 2020

- Walton and Darkes-Sutcliffe, British Education Research Association, 2021